Monday, January 31, 2011

Dwimmermount, Sessions 60-61

The question then became how Candor ought to proceed. He had been given the means to start up a cult devoted to the Iron God and he knew that doing so would speed his recovery from the wounds he received in his long-ago struggle with Orcus. But how does on go about starting a new religion, especially when doing so might well arouse the ire of already-established religions? Likewise, where does one find worshipers? After much discussion, Candor and Dordagdonar -- who finds the whole matter of human religion somewhat baffling -- concluded that it might be best to create the first shrine to the Iron God in a location far from Adamas, a place that could be kept secret. Odd as it seemed, the most logical location were the Thulian crypts that once held the zombie horde that ravaged the countryside months ago. Properly blessed, they'd be sufficiently far away and hidden that they could be made to serve.

As to worshipers, the idea was hit upon to possibly use the gate to the Red Planet of Areon to travel there and spread the word of the Iron God among the slaves of the Eld. After all, the Eld consort with demons and undead alike, two foes of the Iron God. To the downtrodden of Areon, the Iron God's teachings might well hold appeal. The problem, of course, was surviving long enough on the Red Planet to be able to effect any change, let alone change far-reaching enough to result in devotees of the Iron God. Of course, Dordagdonar had his own reasons for suggesting a trek to Areon. After the recent revelations regarding the dwarves and their relationship to humanity, the elf has begun to suspect that the history of his own people may not be quite as he had been told. He's begun to take an interest in alternative versions of elven history and feels that there may be hidden knowledge on the Red Planet that will shed some light on the past.

Before doing any of this, though, the party returned briefly to Dwimmermount to revisit the temple of the Iron God within it. There, they removed the great statue of the god and placed it within a bag of holding so that it could be easily transported to its eventual home in the crypts north of Adamas. While there, Candor, Dordagdonar, Dr. Halsey, and Brother Marius also made use of the arcane device that can transport people to the realm of Xaranes the Iron God. Brother Candor had some further questions to ask of him, as did Dordagdonar. More to the point, it simply seemed wise to consult with the Iron God prior to undertaking this grand plan to establish a new cult in his name.

Upon arriving in the otherworld where Xaranes dwells, the party found him up and active -- a remarkable change from their previous encounter with him. He was surprised to see the visitors and initially did not remember them. It was only after his memory was jogged that he recalled their having come before. He explained once again that time "flows differently" for him than it does "within the sphere" and that often made it hard for him to tell if he'd already met someone or if his meeting was still to come in the future. When Brother Candor asked how some of his wounds had healed, Xaranes explained that he had been receiving "positive energy" sent via the statue. He began to thank Candor for his role in this, but Candor quickly told him that he had yet to establish a cult in his name and so had no part in his healing. Xaranes was genuinely puzzled by this and pointed out that he was receiving aid through one of his statues, a comment that raised further questions, as Candor had mistakenly believed that the statue formerly in Dwimmermount was the only one in existence. Xaranes denied that this was so and stated that there was one near the city they called Yethlyreom.

Needless to say, this caused quite a shock to the PCs, who then decided that they'd need to investigate the location of this other statue. Before doing so, though Dr. Halsey took the time to ask some questions of the Iron God as well. In particular, he wanted to know how he could get home, to which the Iron God shrugged. Xaranes admitted that it was possible to travel "between parallel spheres" but that this technology originated "with the Ancients" and was not one to which he personally had access. The PCs had never heard of "the Ancients" before and Xaranes provided little information about them, except to say that they "existed before" and it was they who had driven the Eld to Areon, a detail that contradicted the accepted history of the Thulians' role in overthrowing the Eldritch Empire and establishing their own in its place. Xaranes did suggest that the Eld might still retain such knowledge, as did the his own masters, the Makers, but obtaining it would take much effort.

Filled with even more questions, the party then made use of the Iron God's transportation device to journey to the location of the other of his statues. They found themselves in a dark and damp cavern, filled with melted candles and showing evidence of having been used recently as a worship site. Dordagdonar suggested they were in a natural cave somewhere along the Ildhon River that ran past Yethlyreom. Further exploration uncovered a concealed door (behind a false stone) that led into a small archive filled with books and scrolls of all sorts. The archive was inhabited by a middle aged man named Alzo, who was overjoyed to see Brother Candor, whom he immediately took to be a messenger from the Iron God (owing to his plate armor and the holy symbol he bore).

Alzo answered many questions from the PCs, explaining that there'd been a cult of the Iron God in Yethlyreom for several centuries. Indeed, the city was once devoted to his faith but it was overthrown in the wreck of the Thulian Empire, when the ruling necromancers decided that all religion had been tainted by the Termaxians, even though that of the Iron God was one of the few that had stood comparatively firm against the pretensions of the followers of Turms. The local cult was small and had recently suffered some setbacks after several of its cells were betrayed and its members slain. But the appearance of Brother Candor proved that the Iron God was watching his faithful and was now sending a champion to turn things around!

The Yethlyreom cult was headed by an old woman named Phaedra. Alzo agreed to arrange a meeting between her and Brother Candor, which would take place in the Outer City, where clerics were tolerated. Phaedra was a steely-eyed woman of ancient years and was clearly suspicious of these new arrivals. From talking to her, it soon became clear that, though she knew much, she wasn't quite as well informed about the Iron God as was Candor. She did, however, know that Xaranes was no god but some other type of being -- "a magically potent man, perhaps" -- which is why she interrogated Candor as to his intentions. Phaedra seemed doubtful that an individual who had previously devoted himself to one of the Thulian gods would now abandon it to serve as an evangelist for a being they both knew was no deity. And Candor quickly got the sense that she was herself more devoted to using the cult as a tool to overthrowing the ruling necromancers than to tenets of the Iron God.

The conversation was a frank one and Phaedra agreed to cooperate with Candor "in matters of mutual interest." He taught her how to communicate between the statues, allowing the two cults to stay in contact with one another. At the same time, Phaedra suggested that Brother Candor stay away from Yethlyreom for a while. If he and his companions were ever needed, she would get in touch with them, but she implied that he would have other matters to keep him occupied. To this, Candor agreed, explaining to her that he felt some kind of change was coming to the world and the Iron God would play a major role in this change. Phaedra admitted that she, too, felt the future would soon be upon them, though she had no idea what it would bring.

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Colour Out of Space

West of Arkham, the hills rise wild, and there are valleys with deep woods that no axe has ever cut. There are dark narrow glens where the trees slope fantastically, and where thin brooklets trickle without ever having caught the glint of sunlight. On the gentler slopes there are farms, ancient and rocky, with squat, moss-coated cottages brooding eternally over old New England secrets in the lee of great ledges; but these are all vacant now, the wide chimneys crumbling and the shingled sides bulging perilously beneath low gambrel roofs.So begins H.P. Lovecraft's favorite of his own stories, "The Colour Out of Space," first published in the September 1927 issue of Hugo Gernsback's Amazing Stories. Amazing Stories has the distinction of being the first pulp magazine devoted solely to science fiction, though, at this early date, "science fiction" is a broad category and includes many stories, such as Lovecraft's own, that, by today's more rigid definitions, would not be considered part of the genre. Nevertheless, "The Colour Out of Space" is not a tale of the supernatural and, even moreso than most of HPL's works, it's quite clear that the events it describes occur because of purely physical causes, albeit alien and inexplicable ones. This probably explains why Lovecraft was so fond of the story: it was an unambiguous exemplar of his philosophy of cosmicism.

"The Colour Out of Space" is a typically Lovecraftian first-person account by a man of learning, in this case a surveyor sent out by the city of Arkham to look for a suitable location for a new reservoir. In doing so, the narrator discovers that the area seemingly most suitable for this project is deemed "evil" by the local inhabitants and rightly so:

It was morning when I saw it, but shadows lurked always there. The trees grew too thickly, and their trunks were too big for any healthy New England wood. There was too much silence in the dim valleys between them, and the floor was too soft with dank moss and matting of infinite years of decay.Moving on, the narrator finally gazes upon the blasted heath itself.

In the open spaces, mostly along the line of the old road, there were little hillside farms; sometimes with all the buildings standing, sometimes with only one or two, and sometimes with only a lone chimney or fast-filling cellar. Weeds and briers reigned, and furtive wild things rustled in the undergrowth. Upon everything was a haze of restlessness and oppression; a touch of the unreal and the grotesque, as if some vital element of perspective or chiaroscuro were awry.

I knew it the moment I came upon it at the bottom of a spacious valley; for no other name could fit such a thing, or any other thing fit such a name. It was as if a poet had coined the phrase from having seen this one particular region. It must, I thought as I viewed it, be the outcome of a fire; but why had nothing new ever grown over those five acres of grey desolation that sprawled open to the sky like a great spot eaten by acid in the wood and fields? It lay largely to the north of the ancient road line, but encroached a little on the other side. I felt an odd reluctance about approaching, and did so at last only because my business took me through and past it. There was no vegetation of any kind on that broad expanse, but only a fine grey dust or ash which no wind seemed ever to blow about. The trees near it were sickly and stunted, and many dead trunks stood rooting at the rim.I quote these passages to give some sense of the tenor of "The Colour Out of Space," which is more an evocation of mood than a conventional narrative. Here, Lovecraft's ability not merely to describe but to conjure up feelings of tension and unease is in full force -- little wonder, then, he regarded the piece so highly.

Like so many of Lovecraft's protagonists, the surveyor is something of a skeptic, believing that "the evil must be something which grandams had whispered to children through centuries" rather than something more real. Still, he is curious about the blasted heath and his curiosity eventually leads him to octogenarian Ammi Pierce, whose "eyes drooped in a curious way" and whose "unkempt clothing and white beard made him seem very worn and dismal." Pierce explains the true origins of the blasted heath, recounting what he remembers from his younger days.

It all began, old Ammi said, with the meteorite. Before that time there had been no wild legends at all since the witch trials, and even then these western woods were not feared half so much as the small island in the Miskatonic where the devil held court beside a curious stone altar older than the Indians. These were not haunted woods, and their fantastic dusk was never terrible till the strange days. Then there had come that white noontide cloud, that string of explosions in the air, and that pillar of smoke from the valley far in the wood. And by night all Arkham heard of the great rock that fell out of the sky and bedded itself in the ground beside the well at the Nahum Gardner place. That was the house which had stood where the blasted heath was to come -- the trime white Nahum Gardner house amidst its fertile gardens and orchards.To my mind, Lovecraft better marshals his talents to set a mood in "The Colour Out of Space" than he does in many of his more famous tales. His vocabulary is much more restrained and the sentence structure not quite so baroque. Likewise, he leaves much unexplained and suggestive, allowing the reader to attempt to piece together the truth of just what happened to Nahum Gardner and his family as a result of the meteor strike. Likewise, the conclusion of the entire story, as the narrator himself reflects on the implications of Ammi Pierce's tale, is similarly suggestive, leaving it to the reader to grapple with its meaning -- if any -- for himself.

Consequently, "The Colour Out of Space" is a very good story and by any measure one of Lovecraft's most effective. Granted, not a lot happens in the story, especially to the story's contemporary narrator, but that's not really the point of it. In a letter to Clark Ashton Smith shortly after completing it, HPL called "The Colour Out of Space" an "atmospheric study" and so it is. It's a well-done evocation of not so much fear or horror as dread, because the reader already knows from the first what will happen to the Gardner farm but he does not know how. Lovecraft deftly makes use of this fact to create one of his best stories and one of the most potent examples of his worldview given literary form.

Saturday, January 29, 2011

Alignment in C&S

Alignment should not be regarded as meaning that Lawful and Chaotic characters must immediately attack each other, or even that they have a "right" to do it. It is in fact possible for characters of opposite Alignment to develop deep respect for each other, and friendship is not impossible. Even the most Chaotic of characters will have his code of honour. Alignment is merely a guide to players so that they can build their character's personality in an orderly manner.There's lots to comment upon here, but what I immediately notice is that the first sentence is phrased negatively: "Alignment should not be regarded ..." That right there is why I have not yet abandoned my initial impression that C&S is parasitic upon Dungeons & Dragons and the culture surrounding it. C&S is implicitly setting itself up in opposition to the way things are done in D&D, or at least the way many players of D&D did things at the time (circa 1977). I won't go so far as to say C&S is unintelligible without first understanding D&D, but I do think it makes more sense within that context.

Given that Lawful characters are noted as "serving the forces of Good" and Chaotic characters are said to "opt for dishonesty, evil, and treachery," I'm not really sure on what basis the authors can claim Lawful and Chaotic characters might develop deep respect for and even friendship with one another. That seems implausible to me, but perhaps I am placing too much emphasis on the thumbnail descriptions of each alignment. As it turns out, C&S has 15 alignments, grouped into the three broad categories of Lawful, Neutral, and Chaotic.

- Lawful: Saintly, Devout, Good, Virtuous, Worthy, Trustworthy, Honourable.

- Neutral: Law Abiding, Worldly, Corruptible.

- Chaotic: Unscrupulous, Base, Immoral, Villainous, Diabolic.

Oh yes: alignment is determined randomly by a 1D20 roll. 8 out of 20 rolls will result in a Neutral alignment of some sort, 7 out of 20 in a Lawful one, and 5 out of 20 in a Chaotic one.

Friday, January 28, 2011

Open Friday: Deviant Settings

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Creation Through Play

When TSR published the Forgotten Realms boxed campaign setting, I was quick to purchase a copy. What I remember most clearly about reading it for the first time was how much more detailed were the Dalelands and Waterdeep and surrounds compared to the rest of the setting. Indeed, the Realms struck me as strangely undetailed outside of a few areas and I wondered why at the time. In retrospect, the answer is obvious: Greenwood only detailed those parts of the Realms that he had to as his campaign progressed. The rest was left vague or unexplained, to be picked up later when and if it ever became necessary. That's more or less the exact approach I've adopted in my Dwimmermount campaign, where anything "off the map" remains, for all intents and purposes, unknown, even to me.

What's interesting is that, once upon a time, this was the norm. Dave Arneson's Blackmoor setting, despite being its age, is remarkably limited in its scope, centered as it is on the kingdom of Blackmoor and the territory immediately surrounding it. Information about anything beyond that comparatively small area is sparse, undoubtedly because such information was unneeded in play. The same seems to have been true of Hargrave's Arduin and (initially anyway) Stafford's Glorantha. Conversely, Barker's Tékumel seems to have had a lot of thought put into it outside of the context of actual play in the setting, with Professor Barker going so far as to create extensive socio-cultural (and linguistic) details for places that had little or no impact on the campaigns he refereed.

I'm not quite sure where to place Gygax's Greyhawk setting. Its published form has some relationship to actual play in Lake Geneva, but the relationship is not one-for-one. The World of Greyhawk owes its existence at least in part for a need on the part of TSR to present a sample campaign setting for D&D players to purchase. Most of the later development of the setting has absolutely nothing to do with actual play in Lake Geneva, being created solely to sell products. Dragonlance's Krynn is even more a creature of marketing, being a setting designed by a committee to launch a new brand. Unless I am mistaken, the only parts of it that derive from actual play by anyone involved are its deities, which were inspired by those in Jeff Grubb's OD&D campaign, as outlined in his The Matter of Theology. TSR's 2e era settings have even less grounding in actual play.

I sometimes come across as being opposed to the very idea of published campaign settings and that's not true at all. I have great fondness for many of them and have often used many of them over the years. What I actually object to are settings that don't reflect anyone's actually having used them in campaign play. I dislike settings that exist solely as commercial products without a foundation in play. The early to mid-1990s were therefore to my mind an awful time in the history of Dungeons & Dragons, dominated by the publication of setting after setting conceived from start to finish purely as commercial products and nothing more. So, it's not that I object to publishing campaign settings as such, but it'd be nice if those settings had a history deeper than the project pitch made to fill a hole in a release schedule.

C&S-ian Naturalism?

No matter how "fantastic" the setting, the basic laws of the universe should apply.Here, I think we very strongly see a difference between Gygaxian and C&S-ian naturalism. The Gygaxian variety is more concerned with verisimilitude than with simulation. C&S, on the other hand, is very much about simulation, as even the short passage above demonstrates. Throw in some high-handed rhetoric about players -- and other designers -- who don't know enough physics, chemistry, and biology and it's very easy to see why I had the impression of the game I did back in the day.

This fact about the nature of the universe -- any universe -- has been all too often lost on many game designers and players alike at one time or another. Part of the problem is that many players themselves are still acquiring a working knowledge of basic physics, chemistry, and biology -- as well as any other relevant science. There will be someone out there ready and eager to interject at this point that "it's only a game". I agree, but I will remind him that role games necessarily and inevitably simulate environments. Players have been too thoroughly conditioned by their own life experiences and have acquired enough knowledge about what happens in their own world to make setting it aside far too difficult. It is too much to expect of players to demand that they accept an arbitrary universe conceived by the Game Master which has natural laws too far removed from those of our real world. Water flows downhill, not up. Rocks do not suspend in midair (unless comprised of ferrous material and buoyed up by an electro-magnetic field). Living creatures can be damaged and killed by physical agencies. These are the facts of science. Why should it suddenly be different in a "fantasy" world?

A Game Master bent on violating natural laws should be required to present detailed explanations of the "laws" of his universe which conflict with those we know prior to playing in his world. Any surprises in this area are simply inexcusable.

In this passage at least, Chivalry & Sorcery definitely comes across as the game of guys who take it a little too seriously and look down their nose at those who don't share their degree of obsessiveness. Of course, as with many things, that's not the whole story, as is evident even within the "Designing C&S Monsters" section from which I've quoted. Still, there's no question that C&S was one of those games that appealed primarily to those who'd already played D&D and found it unsatisfying, not because it was confusing or poorly written, but because it wasn't a good enough simulation. It's a game that was, in some sense, somewhat parasitic upon D&D, because it depended on dissatisfaction with D&D as an engine for generating its players.

That's nothing new by any means. Just as Benjamin Jowett was reputed to have said that all of Western philosophy consists of a series of footnotes to Plato, so too one might argue that all of RPG design consists of a series of footnotes to Gygax and Arneson. C&S definitely feels that way to me, at least right now, but I reserve the right to change my opinion as I absorb more of these fascinating rulebooks.

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Retrospective: Diplomacy

I've readily admitted that I am not now nor have I ever been a wargamer in any meaningful sense. With the exception of some microgames and a handful of "bookshelf games," I simply lack the gene for wargaming. Or it may simply be that I'm not very good at most wargames. I lack both the patience and strategic-level thought needed for such diversions, which probably explains my limited direct experience with most of them.

I've readily admitted that I am not now nor have I ever been a wargamer in any meaningful sense. With the exception of some microgames and a handful of "bookshelf games," I simply lack the gene for wargaming. Or it may simply be that I'm not very good at most wargames. I lack both the patience and strategic-level thought needed for such diversions, which probably explains my limited direct experience with most of them.There's one significant exception, though, and that's Diplomacy. Of course, some might balk at the notion of calling Diplomacy a "wargame" and there's some justification in this. Diplomacy lacks most of the characteristics of the traditional hex-and-chit wargame. Its map, for example, is divided into seventy-five land and sea regions of varying sizes and movement between them is abstract, as is its combat system. Likewise, combat makes no use of a result table. Indeed, random outcomes of any kind are wholly absent from Diplomacy, since the game doesn't require dice to play. Everything that takes place within the game takes place because of specific decisions made by its players and it's for this reason that Diplomacy is, in my opinion, one of the greatest games ever made.

Designed by Allan B. Calhamer, Diplomacy made its original appearance in 1959, gaining a large following, including many people later associated with the roleplaying hobby, such as Gary Gygax and Len Lakofka. I personally never saw the original version of the game, having been introduced to Diplomacy through the 1976 Avalon Hill edition whose cover art I've included above. Diplomacy was one of those games that everyone involved in the hobby in my area played; it was part of the "background noise" of my gaming in the late 70s and early 80s. Because the game requires a minimum of five players and works best with a full seven, it wasn't a pickup game. You needed to work hard to get a game going, but it was usually worth the effort and there was no shortage of people interested in playing. In high school, I played a lot of Diplomacy with my friends and we'd often gather at one another's houses on the weekends specifically to do so. In college, my roommate ran a slow-motion one-move-per-week Diplomacy game with some of our friends and it was a lot of fun too.

The genius of this game are its simple concept and rules. Each player controls one of the Great Powers of pre-World War I Europe: Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, or Turkey. Each Great Power controls several regions on the map, some of which are designated "supply centers." For every supply center a player controls, he may build either an army or a fleet with which to conquer more territory (and thus gain more supply centers). If a player loses control of a region with a supply center and, at the end of his turn, has more military units in play than he has supply centers, he must disband any excess units. Outright victory comes when a player acquires 18 or more centers, though many games end in draws, as two (or occasionally more) players decide the game has dragged on long enough without any clear winner.

As noted, there are no dice in Diplomacy. Everything that occurs does so because a player chooses to make it happen. However, especially in the early stages of the game, most actions require the assistance of other players for success and therein lies the essence of the game. In between turns, players are expected to negotiate with other players for support in their own plans. Thus, treaties and alliances are not only commonplace but expected play elements. Of course, so are betrayals, as no one is required to abide by the terms of anything to which they agree, though players with a reputation for treachery soon find themselves popular targets of others' ire. Consequently, good Diplomacy games are a conflict between the need for others and naked self-interest, which creates a terrific dynamic.

It's easy to see why so many early roleplayers were involved with Diplomacy -- it's practically a roleplaying game itself. Goodness knows my friends and I treated it that way on more than a few occasions, penning our orders in elaborate fashions as if they'd been written by ministers in service to fanciful European monarchs. Silly though this was, it added considerably to our fun and I suspect it helped to lighten the mood of the game, which, as anyone who's ever played can tell you, can sometimes turn quite cutthroat.

I haven't played Diplomacy in many years, but I'd like to. The problem is finding six others with whom to do it and the time to set aside for it. As I understand it, the game is still published by Wizards of the Coast as part of its Avalon Hill brand and I appreciate that. The game is also avidly played by mail, which I find delightful, and on the Internet, thanks to the simple nature of its rules and its emphasis on human interaction as the driver of its events. To my mind, that remains the real genius of Diplomacy: its emphasis on human interaction and player skill, two traits old school roleplaying games have in common with it.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

Intriguing C&S Quotes

For the moment, though, I just wanted to share a couple of quotes. The first is from Scott Bizar's introduction to the rulebook:

Chivalry & Sorcery is the most complete rule booklet ever published. Its very completeness creates problems in the mass of rules to be absorbed. However, the useful suggestions within the rules for how to run a C & S campaign will more than compensate for any difficulty in mastering the volume of rules.In his introduction to The Chivalry & Sorcery Sourcebook published a year later (1978), Bizar's introduction begins with the following:

In the summer of 1977, when we first released Chivalry & Sorcery, we believed that we had published a truly complete game that would never need a supplement. That the book you are now reading exists, demonstrates how wrong we were. C & S is indeed the most complete game ever created, but it is an ongoing campaign and new aspects of the campaign are constantly coming to light and need codification. For these reasons we have created the Sourcebook.Now, on one level, it's amusing to see Scott Bizar attempt to recast his original boast about the completeness of C&S. It's a very easy thing to do, too, since he frequently made such statements about FGU's games (something similar is said in his introduction to Space Opera, for example). On the other hand, pay attention to what he says about C&S being "an ongoing campaign." It's an odd statement on the face of it, but makes more sense when you realize that, as authors Simbalist and Backhaus made clear in the original rulebook, the game is actually a codification of a system created by the University of Alberta's Fantasy Wargames Society to address problems they had with the lack of context for "dungeon and wilderness adventures," which is to say, problems they had with Dungeons & Dragons.

As I understand it, the earliest version of C&S was, like so many early RPGs, a set of house rules for OD&D and the story goes that Simbalist and Backhaus initially thought of submitting their work to TSR for publication as a supplement to D&D. That didn't happen for a variety of reasons (I've heard at least two versions of the tale) and Chivalry & Sorcery as an independent game was born. But the process of house ruling that had led to the creation of this game out of OD&D was still ongoing, even after the rulebook was published in 1977. Simbalist and Backhaus were still playing their campaign and still adding new rules and clarifying existing ones. That's what Scott Bizar was referring to in his introduction to The Sourcebook.

You know what? I find this really appealing. It suggests that C&S was a game that was actually played rather than having been designed solely for the purpose of being sold. It's not a consumer product but a product of passion. That's why I love OD&D's supplements so much (the first three anyway), which feel as if they were the results of someone's having used the LBBs and, through play, come up with new options, additions, and modifications to them. To my mind, that's how an RPG should be developed, not according to a preplanned product schedule created independent of -- or in contradiction to -- actual play. I realize that adopting such an attitude would pretty much doom roleplaying to being a largely hobbyist endeavor, but would that be such a bad thing?

Especializações

In the game, there are only four classes: cleric, fighting man, magic-user, and thief. However, each of the classes also has one or more specialties, often alignment-based, that a player can choose for his character once he's reached 5th level. These specialties minor but flavorful tweaks to the class's normal abilities to represent what in some editions would be a sub-class. For example, a Neutral cleric is a druid, one of whose abilities is to control forest animals, an ability that replaces the turning of undead but uses the same game mechanics to do so. Meanwhile, a Chaotic cleric is a cultist -- I actually like that name better than "anti-cleric" -- and gains the ability to control the undead under certain circumstances. The changes to the base classes are generally fairly small, but I think they're conceptually significant enough to matter in actual play. That's what I like about the design of Old Dragon, from what I've read so far: it does a lot with only a few minor tweaks to the familiar rules of Dungeons & Dragons.

In the interests of inspiring others, here's a listing of all the specialties in Old Dragon:

- Cleric: Druid (Neutral), Cultist (Chaotic)

- Fighting Man: Paladin (Lawful), Warrior (Neutral), Barbarian (Chaotic)

- Magic-User: Illusionist (Neutral), Necromancer (Chaotic)

- Thief: Ranger (Lawful), Explorer (Lawful), Bard (Neutral), Assassin (Chaotic)

I'll likely talk more about this game in the days to come, but it's slow-going for me, since, as I said, my command of Portuguese is limited. Still, I've been enjoying this game a great deal, so it's well worth having to move slowly, dictionary in hand, as I make my way through it.

Monday, January 24, 2011

Pulp Fantasy Library: I Remember Lemuria

Since I mentioned Richard S. Shaver in my post last week on the occasion of Abraham Merritt's birthday, I thought it only right to devote this week's installment of Pulp Fantasy Library to him. In that post, I made reference to the 1947 tale "The Shaver Mystery," while indeed famous, was not Shaver's first tale of his experiences a the secret subterranean world. That distinction belongs to "I Remember Lemuria," which was first published in the March 1945 issue of Amazing Stories and proved to be one of the best-selling issues in the magazine's history.

Since I mentioned Richard S. Shaver in my post last week on the occasion of Abraham Merritt's birthday, I thought it only right to devote this week's installment of Pulp Fantasy Library to him. In that post, I made reference to the 1947 tale "The Shaver Mystery," while indeed famous, was not Shaver's first tale of his experiences a the secret subterranean world. That distinction belongs to "I Remember Lemuria," which was first published in the March 1945 issue of Amazing Stories and proved to be one of the best-selling issues in the magazine's history.There are a lot of reasons why "I Remember Lemuria" generated such a positive response with readers, but perhaps the most likely is that it doesn't present itself as fiction at all, a pose that is aided by its copious accompanying footnotes, most of which were supplied by Amazing's editor, Ray Palmer. For example, here's a long footnote on the deros:

Pressed for a more complete explanation, Mr. Shaver has defined "dero' for us:That's a pretty representative example of what the footnotes accompanying this story are like, though some are shorter and a few are even longer. Reading them gives the impression that the editor believes every word of what Shaver has written and that he endorses it as true. As it turns out, Ray Palmer did believe this, or at least publicly claimed to do so. There's apparently some question as to whether Palmer's beliefs were merely a marketing ploy intended to sell more copies of Amazing Stories and other books relating to Shaver's wild theories."Long ago it happened that certain (underground) cities were abandoned and into those cities stole many mild mortals to live, At first they were normal people, though on a lower intelligence plane; and ignorant due to lack of proper education. It was inevitable that certain inhabitants of the culture forests lose themselves and escape proper development; and some of them are of faulty development. But due to their improper handling of the life-force and ray apparatus in the abandoned cities, these apparatii became harmful in effect. They simply did not realize that the ray filters of the ray mechanisms must be changed and much of the conductive metal renewed regularly. If such renewals are not made, the apparatus collects in itself—in its metal—a disintegrant particle which gradually turns its beneficial qualities into strangely harmful ones.

"These ignorant people learned to play with these things, but not to renew them; so gradually they were mentally impregnated with the persistently disintegrative particles. This habituates the creature's mind, its mental movements, to being overwhelmed by detrimental, evil force flows which in time produce a creature whose every reaction in thought is dominated by a detrimental will. So it is that these wild people, living in the same rooms with degenerating force generators, in time become dero, which is short for detrimental energy robot.

"When this process has gone on long enough, a race of dero is produced whose every thought movement is concluded with the decision to kill. They will instantly kill or torture anyone whom they contact unless they are extremely familiar with them and fear them. That is why they do not instantly kill each other—because, being raised together, the part of their brain that functions has learned very early to recognize as friend or heartily to fear the members of their own group. They recognize no other living thing as friend; to a dero all new things are enemy.

"To define: A dero is a man who responds mentally to dis impulse more readily than to his own impulses. When a dero has used old. defective apparatus full of dis particle accumulations, they become so degenerate that they are able to think only when a machine is operating and they are using it; otherwise they are idiot. When they reach this stage they are known as 'ray' (A Lemurian word not to be confused with ray as it is used in English.) Translated, ray means 'dangerous or detrimental energy animal.' Ray is also used to mean a soldier—one of those who handles beam weapons (note how the ancient meaning has come into our modern word)."—Ed.

"I Remember Lemuria" owes its origin to a letter that Shaver wrote to Palmer sometime in 1943. In that letter, Shaver claimed to have learned how to understand an ancient language (called Mantong) that was not only the root of other human languages but also worked as a cipher for decoding the deeper meanings hidden within those languages. Intrigued, Palmer asked to hear more about Shaver's discovery and the two exchanged many letters that resulted in Palmer's becoming convinced of the truth of Shaver's claims. Shaver eventually sent Palmer a large document describing a secret underground world filled with ancient races and powerful technologies. Palmer then reworked this document into the even-larger first person account of Mutan Mion, an ancient inhabitant of Sub Atlan (subterranean Atlantis), to whose memories Shaver somehow had access. "I Remember Lemuria" thus presents itself as an eyewitness account of the final days of Sub Atlan, before most of its people leave it and the Earth behind for a new home on "a planet with untouched coal deposits located near the Nortan group of planets."

As silly as this all may sound, "I Remember Lemuria" is strangely compelling. Just as Mantong is supposedly the root of all human languages, so too is this story the root of so many modern day occult conspiracy theories. A big part of what makes it so compelling is the absolute conviction with which Shaver (and Palmer) present this story. He's so adamant about the reality of what he's presenting that one can't help but wonder, if only briefly, if he really did experience something he can't explain. As he says in his foreword:

I myself cannot explain it. I know only that I remember Lemuria! Remember it with a faithfulness that I accept with the absolute conviction of a fanatic. And yet, I am not a fanatic; I am a simple man, a worker in metal, employed in a steel mill in Pennsylvania. I am as normal as any of you who read this and gifted with much less imagination than most of you!Is it any wonder, then, that "I Remember Lemuria" and the stories that followed (such as "The Shaver Mystery") proved so popular with readers of Amazing Stories and inspired a craze about the hollow earth and its supposed inhabitants? I'm pretty sure Richard Shaver was crazy, but his ravings are nevertheless intriguing and inspirational and I can't deny that I've turned to him on more than one occasion when looking for ideas. I'm sure I'm not the only one.What I tell you is not fiction! How can I impress that on you as forcibly as I feel it must be impressed? But then. what good to impress it upon those who will crack wise about me being a "sharp-shaver"? I can only hope that when I have told the story of Mutan Mion as I remember it you will believe—not because I sound convincing or tell my story in a convincing manner, but because you will see the truth in what I say, and will realize, as you must, that many of the things I tell you are not a matter of present day scientific knowledge and yet are true!

I fervently hope that such great minds as Einstein, Carrel, and the late Crile check the things that I remember. I am no mathematician; I am no scientist. I have studied all the scientific books I can get—only to become more and more convinced that I remember true things. But surely someone can definitely say that I am wrong or that I am right, especially in such things as the true nature of gravity, or matter, of light, of the cause of age and many other things that the memory of Mutan Mion has expressed to me so definitely as to be conviction itself.

I intend to put down these things, and I invite—challenge!—any of you to work on them; to prove or disprove, as you like. Whatever your goal, I do not care. I care only that you believe me or disbelieve me with enough fervor to do some real work on those things I will propound. The final result may well stagger the science of the world.

Saturday, January 22, 2011

In Memoriam: Robert Ervin Howard

It is hard to sum up any man in but a few words, even moreso when the man in question is Robert Ervin Howard, who was born on this day in 1906. Rather than attempt to do so, I instead offer up this excerpt from H.P. Lovecraft's tribute to him, published in the September 1936 issue of Fantasy Magazine:

It is hard to sum up any man in but a few words, even moreso when the man in question is Robert Ervin Howard, who was born on this day in 1906. Rather than attempt to do so, I instead offer up this excerpt from H.P. Lovecraft's tribute to him, published in the September 1936 issue of Fantasy Magazine:The character and attainments of Mr. Howard were wholly unique. He was, above everything else, a lover of the simpler, older world of barbarian and pioneer days, when courage and strength took the place of subtlety and stratagem, and when a hardy, fearless race battled and bled, and asked no quarter from heartless nature. All his stories reflect this philosophy, and derive from it a vitality found in few of his contemporaries. No one could write more convincingly of violence and gore than he, and his battle passages reveal an instinctive aptitude for military tactics which would have brought him distinction in times of war. His real gifts were even higher than the readers of his published works would suspect, and had he lived, would have helped him to make his mark in serious literature with some folk epic of his beloved southwest.Well said, Mr Lovecraft, and happy 105th birthday, Mr Howard.

It is hard to describe precisely what made Mr. Howard's stories stand out so sharply, but the real secret is that he himself is in every one of them, whether they were ostensibly commercial or not. He was greater than any profit-making policy he could adopt -- for even when he outwardly made concessions to Mammon-guided editors and commercial critics, he had an internal force and sincerity which broke through the surface and put the imprint of his personality on everything he wrote. Seldom, if ever, did he set down a lifeless stock character or situation and leave it as such. Before he concluded with it, it always took on some tinge of vitality and reality in spite of popular editorial policy -- always drew something from his own experience and knowledge of life instead of from the sterile herbarium of dessicated pulpish standbys. Not only did he excel in pictures of strife and slaughter, but he was almost alone in his ability to create real emotions and spectral fear and dread suspense. No author -- even in the humblest fields -- can truly excel unless he takes his work very seriously, and Mr. Howard did just that in cases where he consciously thought he did not. That such an artist should perish while hundreds of insincere hacks continue to concoct spurious ghosts and vampires and space-ships and occult detectives is indeed a sorry piece of cosmic irony!

Friday, January 21, 2011

Open Friday: Published or Home Brew?

I've done both over the years, though it's interesting to note that, in my earliest days of gaming, I always homebrewed, just as I have in recent years. It was in my middle years that I was more inclined to use published settings than to make my own. I have no idea if that means anything, but it's an interesting fact nonetheless.

Thursday, January 20, 2011

Delving Deeper

I'm sure the usual suspects are already registering their displeasure over the appearance of yet another retro-clone, but the complainers are forgetting a couple of things. First, all the retro-clones of D&D to date are broadly cross-compatible, so it's not as if BHP's publication of Delving Deeper will suddenly make, say, the adventures John Adams will also publish uncompatible with Labyrinth Lord, Swords & Wizardry, or even Lamentations of the Flame Princess. There's really no harm to anyone who isn't interested in another clone. Second, there are plenty of old school fans who are interested in additional clones, since the best of them all bring something to the table that others don't, whether it's S&W's unified saving throw or LotFP WFRP's encumbrance rules. And since the texts of all these clones are available for free, anyone who just wants to cherry-pick their best ideas without buying them is able to do so with ease. Finally, BHP's White Box was the only boxed, introductory old school RPG out there. Retailing at under $30, it was affordably priced and suitable for a wide audience, from children to adults. That gave it a unique place in the old school market, a place that ought to continue to be filled.

It's worth noting, too, that Delving Deeper looks like it'll cover a couple of related bases. It'll both allow people to play something reminiscent of LBB-only OD&D, as well as, with a few tweaks, something in line with the Holmes Blue Book. I think that's rather unique as well and will help to distinguish DD from both White Box and the other existing clones. So, from my admittedly biased perspective, I don't really see a downside to this announcement, especially since Matt Finch has stated elsewhere that he intends to continue to make WB readily available in some form, for those who prefer that version to Swords & Wizardry. What's not to like?

Merritt and Memory

Regular readers of this blog know well that one of its well-worn themes is the lack of appreciation for the authors who inspired the founders of our collective hobby. Since today is the 127th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Grace Merritt, whose works Gary Gygax listed among the "most immediate influences upon AD&D" alongside more widely lauded authors such as Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, Jack Vance, and H.P. Lovecraft, it seemed as good a time as any to tilt once more against the windmill of cultural amnesia.

Regular readers of this blog know well that one of its well-worn themes is the lack of appreciation for the authors who inspired the founders of our collective hobby. Since today is the 127th anniversary of the birth of Abraham Grace Merritt, whose works Gary Gygax listed among the "most immediate influences upon AD&D" alongside more widely lauded authors such as Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, Jack Vance, and H.P. Lovecraft, it seemed as good a time as any to tilt once more against the windmill of cultural amnesia.Merritt's obscurity to contemporary readers may be because he produced comparatively few works of fiction. By profession, he was a journalist and editor rather than an author, working for most of his career for The American Weekly. Indeed, he was one of the most successful -- and highly paid -- journalists of his era, making, according to Sam Moskowitz, $25,000 a year in 1919 and $100,000 a year at the time of his death in 1943. It's little wonder, then, that Merritt wrote far fewer stories than, say, Lovecraft or Howard. That he nevertheless did so testifies, I think, to Merritt's passion for the fantastic and the weird, a passion that shines through in his best stories. He used his wealth to travel the world, seeking out the strange (he was an early member of the original Fortean Society) and he assembled a large library of the occult.

H.P. Lovecraft was a great admirer of Merritt and even had occasion to meet him in person in 1934, while he was visiting New York, where he maintained a home on Long Island. He describes his impressions of the man in a contemporary letter to Robert H. Barlow:

I really had a delightful time — seeing all the old gang… But the meeting which will interest you most is that with A. Merritt, the Moon Pool man. It seems he had long known my work and held a very kindly opinion of it. Hearing of my presence in NY he took steps to get in touch with me, and finally invited me to dinner at his club — the Players, which occupies Edwin Booth’s old home in Gramercy Park. Merritt is a stout, sandy, grey-eyed man of about 45 or 50 — extremely pleasant and genial, and a brilliant and well-informed conversationalist on all subjects. He is associate editor of Hearst’s American Weekly, but all his main interests centre in his weird writing. He agrees with me that the original Moon Pool novelette in the All-Story is his best work. Just now he is doing a sequel to Burn, Witch, Burn (which I haven’t read, but which he says he’ll send me), whose locale will be the fabulous sunken city of Ys, off the coast of Brittany. It will bring in the comparatively little-known legendry of shadow-magic. Merritt has a wide acquaintance among mystical enthusiasts, and is a close friend of old Nicholas Roerich, the Russian painter whose weird Thibetan landscapes I have so long admired. I was extremely glad to meet Merritt in person, for I have admired his work for 15 years. He has certain defects — caused by catering to a popular audience — but for all that he is the most poignant and distinctive fantaisiste now contributing to the pulps. As I mentioned some time ago — when you lent me the Mirage installment — he has a peculiar power of working up an atmosphere and investing a region with an aura of unholy dread.I like this passage in HPL's letter not just because of what it says about Merritt as a writer but as a man. By all accounts, Merritt was a pleasant, well-read, and unpretentious person who did not allow his success to distance him from the things he loved. One of America's highest-paid journalists, who used his influence to, for example, promote the work of then-controversial physical therapy pioneer Elizabeth Kenny (which, coincidentally, greatly aided the creator of the Illuminatus! trilogy, Robert Anton Wilson, as a child), Merritt neither felt shame nor saw any contradiction in his weird fictional side career -- an attitude I find laudable and wish more gamers might adopt as their own.

There are many common themes in Merritt's fiction, most notably lost races and subterranean realms. Such ideas are commonplace now, in part because of the role Merritt played in promoting them, both through his fiction and his editorial work on The American Weekly, which often included stories of scientific "marvels" and inexplicable events. Lovecraft readily acknowledged the debt he owed to Merritt's stories, particularly The Moon Pool (which, interestingly, was also noted by Gygax as a favorite of his), so there's a sense in which the Mythos as it came to be might not have existed without Merritt. Similarly, Richard Shaver, most famous for having written "The Shaver Mystery" in 1947, seems to have believed that Merritt's stories were not in fact fiction but rather fictionalized accounts of things Merritt had actually experienced while on his world travels. Shaver's own theories of subterranean realms and ancient races were themselves widely influential, including on Dungeons & Dragons, whose derro race is certainly derived from Shaver's own "dero" (short for "detrimental robot," called such because of their robot-like behavior).

In my opinion, both Merritt and his fiction deserve much wider recognition than either has received in recent years. The more I learn about him and his life, the more fascinated I've become and his fiction, while not of universally high quality, nevertheless contains enough excellent entries to justify spending the time to read them. That he was claimed as an influence by many of fantasy and science fiction's luminaries (not to mention Gary Gygax) is another reason to give him a look, if you've never done so. I don't think you'll regret it.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

In Case You Missed It ...

Two Common Complaints

I'd wager that the primary reason we've not yet seen another Empire of the Petal Throne (though I think we've seen plenty of Blackmoors) is that there's not much interest in such a thing. If the history of the hobby has taught us anything, it's that "vanilla fantasy" will always be a bigger draw than something more outré. Tékumel, which I love dearly and consider one of the finest works of 20th century fantasy in any medium, has had a lot of kicks at the can, going all the way back to 1975. If there were a huge, pent-up demand among gamers for something like it, I suspect Tékumel would have been more widely known and used for RPGs. Ditto for Jorune, Talislanta, and many, many other very fine games that are probably more talked about than actually played.

Lest I be misunderstood -- goodness knows that's never happened before -- I'm not denigrating the notion of something other than vanilla fantasy or the desire to see "new" old school RPGs. My point is simply that gamers like what they like and, if we haven't seen enough "originality" (by whatever measure), it's because most gamers don't actually like that kind of thing. Again, let me be clear: I'm not suggesting that gamers aren't imaginative or interested in ideas that break the mold, but what experience has shown me is that, when forced to choose between a game/setting that's closer to what they're familiar with and one that's not, they'll choose the former by a large margin in most cases. Those who prefer the exotic will always be a minority and, more to the point, there's no way to predict what game will finally be the one that makes a breakthrough.

This brings me to the second complaint, namely that the old school renaissance is "too D&D-centric." Quick quiz: what's the most popular tabletop RPG in 2011? How about 2001? 1991? 1981? The answer now, as it has been since 1974, is "Dungeons & Dragons" (or some variation thereof, if the claims that Pathfinder is in a dead-heat with D&D IV are at all true). Consequently, it shouldn't surprise anyone that the OSR is dominated by D&D. I've noted before that, when I post about games other than D&D, there are significantly fewer comments. Why? Because now, as in the past, D&D remains the 800-lb. gorilla of gaming, especially so when you're talking about old school gaming.

I'm personally very interested in a lot of other old school RPGs, which is why I'll continue to post about Space Opera and Stormbringer and Bushido when I have some thoughts to share on them. But I recognize the fact that most gamers, even most old school gamers, aren't as interested in these games, many of which are, for all intents and purposes dead and buried. I mean, is there an online community devoted to, say, Universe that I've never heard about? Are there bastions of Superhero 2044 fans hidden away somewhere? It's not like there's a conspiracy on the part of the OSR to exclude these other old school games (or the gamers who love them) from our discussions. It's simply that, from my perspective anyway, there's no interest in them whatsoever, beyond a handful of guys who like to use them to bash the old school renaissance with a convenient club.

Ultimately, as Rob Conley has said again and again, the old school renaissance belongs to those who do. Thanks to the OGL, cheap and easy-to-use layout programs, and print-on-demand, anyone can do what Gary and Dave did back in 1974. We're all empowered to follow our passions and create the games and game material that we want. So, if anyone's frustrated that no one's created another Tékumel or there's no retro-clone of Bunnies & Burrows, that's not the fault of the old school renaissance. By the same token, just because there is an old school renaissance doesn't mean that anything that calls itself "old school" will be embraced enthusiastically. Now, as then, gamers will like what they like. I'm sure Dave Nalle wishes that Ysgarth really took off and became a popular fantasy RPG, but it didn't, because it just didn't catch gamers' fancies back in 1979. That's always been the way of things.

It's now easier than ever to produce and distribute tabletop RPGs and RPG materials, but someone has to create them. Since the old school renaissance is a hobbyist movement made up of individuals rather than a hive mind, it only stands to reason that we get what we get based on the interests of those individuals who're putting forward their creations and sharing them with others. Don't like what's on offer? It's trivial to be able to put one's own stuff out there and that's one of the guiding principles of this crazy little thing we've got going.

With that in mind, and in accordance with the Joeskythedungeonbrawler Protocol, I offer the following from my Dwimmermount campaign. The text in the quote box below is hereby designated Open Game Content via the Open Game License.

Fetish of the Rat King: This small wooden carving of a rat that functions much like a ring of animal control on rodents, but with some differences. First, the number of rodents that can be controlled at any one time is 10-60. Rodents that are inherently magical or possess magical abilities are immune to this item's effects, which last as long as the user concentrates. The user can also speak with and understand the speech of all rodents while possessing the fetish. There is a cumulative 1% chance per use of the fetish to command rodents that the user will be cursed with lycanthropy and become a wererat.

Retrospective: Illuminati

I am nothing if not predictable.

I am nothing if not predictable.Much as I loved and played the heck out of both Car Wars and Ogre, of all the Steve Jackson microgames, it was Illuminati to which my heart truly belonged. First published in 1982, Illuminati was a fast-moving -- and humorous -- card game of secret societies vying with one another for control of the world. Like all the best games, Illuminati was easy to learn and difficult to master and much of its fun came from that most unpredictable of elements -- the players themselves.

Players took on the role of one of several world-spanning conspiracies, such as the Discordian Society, the UFOs, or the Servants of Cthulhu. They attempt to win the game through controlling other "lesser" organizations, from the CIA to the Boy Sprouts to Trekkies, creating a power structure through which they can amass money, power, and influence with which to control even more organizations and, of course, attack opposing conspiracies. Each conspiracy has its own goals and victory comes with achieving those goals. For example, the Gnomes of Zürich need to amass a certain amount of money to win the game, while the Bavarian Illuminati need to amass a certain of power to do so. Some goals are harder to achieve than others, but that, too, is part of the game's lasting appeal, since certain conspiracies could be considered "advanced" options for players looking for a real challenge.

I say that, of all Steve Jackson's microgames, my heart belongs to Illuminati, but that doesn't mean I actually played the game as often as I played the others. Compared to Car Wars and Ogre, Illuminati isn't something you did on a lark. A typical game could take a couple of hours to complete in my experience, because the game involved lots of negotiations and deal making amongst the players, as they formed temporary alliances against one another. This aspect of the game, which I loved, tended to drag out game play and so Illuminati was one of those games you didn't just pick and play while waiting for your friends to arrive. You had to decide in advance to play Illuminati and set aside the time to do so and you needed at least four or five players to get the most out of it.

An aspect of the game that my friends and I always found amusing was looking at the power structures we created through play and imagining a world where it really was the case that the UFOs controlled orbital mind control lasers who controlled the Mafia, who controlled the CIA, who controlled Hollywood, etc. Illuminati power cards were a lot of fun just to read, since, in addition to the name and humorous illustrations on them, they included game statistics, such as power, income, and resistance. Each card also had an alignment such as "liberal," "government," or "violent." Alignment played a big role in the play of the game, since it was always easier for a power group to control another group whose alignment was similar (or at least not opposed) to its own. Reading the alignments is fun too, if only to get some insight into the mind of designer Steve Jackson, whose politics and sense of humor are not always in synch with those of other gamers.

Unlike the previous two SJG microgames I've discussed recently, Illuminati still appears to be available for sale, albeit in a "deluxe" format that incorporates a lot of additional rules and power groups from expansions to the original. I've never played this current version, so I can't say how close it is to the game I played in the early 80s, but I assume there's a fair degree of continuity. Consequently, you can give the game a try yourself, if you're not put off by its $34.95 price tag. I'm half-tempted to pick up a copy myself, since I no longer own my 1982 pocket box edition, but I have to admit that the price and the fact that it's an expanded edition is a bit off-putting to me. In addition to their simplicity, one of the great appeals of those microgames of old was their price and portability. A kid with limited funds could easily afford to buy them and you could carry them anywhere and play. They don't seem to make games like that anymore or, if they do, they're not as widely accessible as these microgames once were and that's a shame.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Jeff Dee and Jack Herman Interview

Thanks to Christian de la Rosa for the tip.

Toronto Old School Mini-Con Update

As of now, wheels are in motion. Someone has graciously stepped forward and is attempting to secure a very nice location for this event. If successful in this, we'll then be ready to move forward to the actual planning stage, including setting a date, etc. Until then, there's not much more that can be done, but I really do appreciate everyone who's offered to pitch in to make this happen. I am not, as I said before, someone who should ever be relied upon to plan, well, anything, let alone a gathering of other people, so I am ever so grateful to those who have both the skills and the drive to do so.

All I can say is that it looks increasingly likely that this will happen. It's just a question of where and when. I have to admit I'm quite excited at the prospect. I honestly didn't think things would come together at all, let alone so quickly, but it's terrific to see such enthusiasm from Toronto area gamers for an old school mini-con.

When I know more, you can be sure I'll be posting it here.

Petty Gods Update

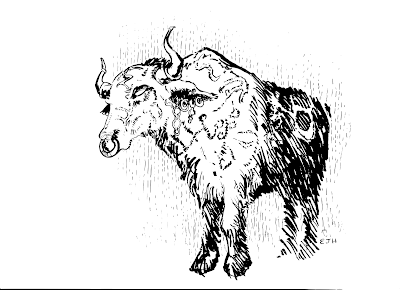

That's Khaldranath the Ox Lord, another petty god who'll be making his appearance once this book is made available.

So, where do things stand on this project? There are still some late submissions I haven't yet looked at, as well as quite a few art descriptions I need to send out. My plan -- and we all know how good I am at following through with such things -- is to sort through the last submissions today. Then I'll final table of contents for the book, which I'll post here in a few days, listing the names of all the gods, their areas of patronage, and their authors, as well as whether I have an illustration for them. That way artists who'd still like to contribute can pick a deity of their choice rather than having one assigned to them by me. My hope is to have the text all done and ready to go by month's end. After that, it's just a question of layout, which in turn depends on having all the illustrations in my hands. Once I do, we're in the home stretch. The final book will be made available as a free PDF or as a for-cost book on Lulu.com.

Let me also state here that, while I plan to release the text of the gods as Open Content under the Open Game License, neither Paul Jaquays's foreword nor any of the artwork are Open Content, with the copyrights to each remaining with their creators. If anyone who contributed to Petty Gods does not want their submission to be released as OGC, please contact me separately and I can accommodate you to the extent it's possible under the OGL. Otherwise, my intention is to release this material to the world in the hopes that others will adopt and adapt some of it in their own games and projects.

Pulp Fantasy Library: The Face in the Abyss

Like a lot of early pulp fantasy novels, Abraham Merritt's The Face in the Abyss originally appeared in a shorter form. First published in the September 8, 1923 issue of Argosy All-Story Weekly, the novelette "The Face in the Abyss" was followed up seven years later with a seven-part sequel (called "The Snake Mother") that picked up where the original left off. Then, in 1931, Merritt combined the two stories under a single cover. It was in this form that I encountered the story sometime in the 1980s, having read that Merritt was an important influence on H.P. Lovecraft.

Like a lot of early pulp fantasy novels, Abraham Merritt's The Face in the Abyss originally appeared in a shorter form. First published in the September 8, 1923 issue of Argosy All-Story Weekly, the novelette "The Face in the Abyss" was followed up seven years later with a seven-part sequel (called "The Snake Mother") that picked up where the original left off. Then, in 1931, Merritt combined the two stories under a single cover. It was in this form that I encountered the story sometime in the 1980s, having read that Merritt was an important influence on H.P. Lovecraft.The Face in the Abyss tells the tale of Nicholas Graydon, who, along with some companions, is on an expedition in the Andes, where they seek to recover the legendary ransom offered to Pizarro for the release of the Incan king Atahualpa. Graydon is a fairly typical Merritt protagonist, upstanding and heroic, while his companions are much more morally dubious, a fact made clear when one of them, Starrett, assaults a native girl they find while seeking the ransom. Graydon, of course, stops him with a swift punch and frees the girl, whose name is Suarra and whose appearance startles him:

Her skin was palest ivory. It gleamed through the rents of the soft amber fabric, like thickest silk, which swathed her. Her eyes were oval, a little tilted, Egyptian in the wide midnight of her pupils. Her nose was small and straight; her brows level and black, almost meeting. Her hair was cloudy, jet, misty and shadowed. A narrow fillet of gold bound her low broad forehead. In it was entwined a sable and silver feather of the caraquenque--that bird whose plumage in lost centuries was sacred to the princesses of the Incas alone.Already, the reader can see where this novel is going but one must remember that, while clichéd now, Merritt was among those who helped to found and popularize the pulp convention of the "lost race," conventions that other authors later adopted as their own. Suarra explains that her people are called the "Yu-Atlanchi" and she is a servant of a being she calls "the Snake Mother." Yu-Atlanchi is ancient, perhaps ancient enough to have co-existed with the dinosaurs, or at least knowledgeable enough about the past to know much about them, as Graydon discovers. Indeed, the Yu-Atlanchi seem to possess very impressive scientific knowledge, far beyond that of 20th century Western civilization.Above her elbows were golden bracelets, reaching almost to the slender shoulders. Her little high-arched feet were shod with high buskins of deerskin. She was lithe and slender as the Willow Maid who waits on Kwannon when she passes through the World of Trees pouring into them new fire of green life.

She was no Indian...nor daughter of ancient Incas...nor was she Spanish...she was of no race that he knew. There were bruises on her cheeks--the marks of Starrett's fingers. Her long, slim hands touched them. She spoke--in the Aymara tongue.

Suarra further explains that her people were once ruled six lords and a higher lord over them, but now only the Snake Mother rules -- "and another." This other is Nimir, the lord of evil, who was once a lord of Yu-Atlanchi but seized power and attempted to make himself a god. Though he failed in fully achieving his dream, he was successful enough that he could not be slain and so his vanquishers trapped his spirit in a stone prison.

Even trapped, Nimir exercises great influence within Yu-Atlanchi, whose people have become decadent over the centuries. Their current leader lives a debauched existence, caring little for his people, and entertaining them with blood sports and other cruelties. Suarra and others like her in "the Fellowship" -- a resistance movement against Yu-Atlanchi's present regime -- believe that Nimir is rising and may soon be able to escape his prison and assume more direct control over the kingdom he once sought.From where he stood a flight of Cyclopean steps ran down into the heart of the cavern. At their left was the semi-globe of gemmed and glittering rock. At their right was — space. An abyss, whose other side he could not see, but which fell sheer away from the stairway in bottomless depth upon depth.

The face looked at him from the far side of the cavern. Bodiless, its chin rested upon the floor. Colossal, its eyes of pale blue crystals were level with his. It was carved out of the same black stone as the walls, but within it was no faintest sparkle of the darting luminescences. It was a man’s face and the face of a fallen angel’s in one; Luciferean; imperious; ruthless — and beautiful. Upon its broad brows power was enthroned — power which could have been godlike in beneficence, had it so willed, but which had chose instead the lot of Satan.

Whoever the master sculptor, he had made of it the ultimate symbol of man’s age-old, remorseless lust for power. In the Face this lust was concentrate, given body and form, made tangible…

And now he saw that all the darting rays, all the flashing atoms, were focused full upon the Face, and that over its brow was a wide circlet of gold. From the circlet globules of gold dripped, like golden sweat. They crept sluggishly down its cheeks. From its eyes crept other golden drops, like tears. And out of each corner of the merciless mouth the golden globules dribbled like spittle. Golden sweat, golden tears and golden slaver crawled and joined a rivulet of gold that oozed from behind the Face, to the verge of the abyss, and over its lip into the depths.

It's a terrific set-up for a surprisingly good pulp novel. As I noted above, one has to be tolerant in reading this today, since so many of its plot points might feel dated and unoriginal to a contemporary reader. At the time of its writing, though, Merritt was blazing new trails and, despite the hackneyed nature of some of the novel's elements, they nevertheless feel fresh in Merritt's hands. Graydon himself is not particularly interesting, I'll grant, but Suarra, the Snake Mother, and even Nimir are fully realized characters that stand head and shoulders above what one usually gets in novels of this kind. Likewise, Merritt's skill at depicting the wonders and horrors of decadent Yu-Atlanchi is superb and I found myself quite enthralled. The Face in the Abyss is definitely a cut above other "lost race" novels and well worth reading, if you've never done so.

Monday, January 17, 2011

Gone Sledding

The weekend was crazy busy, owing in part to a large-ish snowfall and celebrations surrounding my daughter's birthday. So I just took the last few days off and got nothing accomplished other than family-related fun, such as sledding on a hill near our home.

The weekend was crazy busy, owing in part to a large-ish snowfall and celebrations surrounding my daughter's birthday. So I just took the last few days off and got nothing accomplished other than family-related fun, such as sledding on a hill near our home.Regular posting, including this week's installment of Pulp Fantasy Library and updates on Petty Gods will resume this afternoon or evening, depending on how quickly I catch up on various matters that demand immediate attention.

Friday, January 14, 2011

Open Friday: How Many?

In my Dwimmermount campaign, I began with just OD&D's three (cleric, fighting man, magic-user) and eventually allowed a modified thief as an NPC. I also introduced paladins and planned to introduce druids. In principle, I might allow even more classes if the need ever arose, but, so far, it hasn't and the game is primarily an "original three" campaign that's open to more if the exigencies of play demanded it.

How about you?

Thursday, January 13, 2011

The Druids of Dwimmermount, Part III

The text in the quote box below is hereby designated Open Game Content via the Open Game License.

1st Level

1. Cure (Cause) Light Wounds (Cleric)

2. Detect Magic (Cleric)

3. Divine Weather (Druid)

4. Faerie Fire (Druid)

5. Locate Creature (Druid)

6. Purify Food and Drink (Cleric)

2nd Level

1. Find Plant (Druid)

2. Find Traps (Cleric)

3. Heat Metal (Druid)

4. Hold Person (Cleric)

5. Obscuring Mist (Druid)

6. Produce Flame (Druid)

7. Silence 15' Radius (Cleric)

8. Snake Charm (Cleric)

9. Speak with Animals (Cleric)

10. Warp Wood (Druid)

3rd Level

1. Call Lightning (Druid)

2. Cure Disease (Cleric)

3. Cure Disease (Cleric)

4. Dispel Magic (Cleric)

5. Hold Animal (Druid)

6. Locate Object (Cleric)

7. Plant Growth (Druid)

8. Protection from Fire (Druid)

9. Pyrotechnics (Druid)

10. Water Breathing (Druid)

4th Level

1. Cure (Cause) Serious Wounds (Cleric)

2. Hallucinatory Terrain (Druid)

3. Neutralize Poison (Cleric)

4. Passplant (Druid)

5. Produce Flame (Druid)

6. Protection from Electricity (Druid)

7. Speak with Plants (Cleric)

8. Sticks to Snakes

9. Summon Animal I (Druid)

10. Temperature Control (Druid)

5th Level

1. Animal Growth (Druid)

2. Animal Summoning II (Druid)

3. Anti-Plant Shell (Druid)

4. Commune with Nature (Druid)

5. Control Winds (Druid)

6. Hold Vegetation and Fungus (Druid)

7. Insect Plague

8. Transmute Rock to Mud (Druid)

9. Transport via Plants (Druid)

10. Wall of Fire